Absidia

Introduction

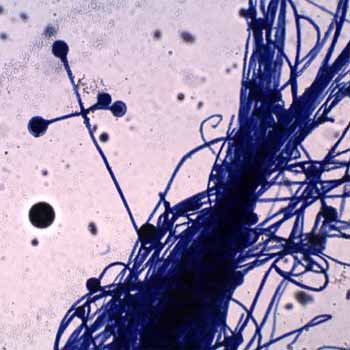

Absidia currently contains 21 mostly soil-borne species. A. corymbifera is the only species of Absidia known to cause disease in man and animals. Colonies are fast growing, floccose, white at first becoming pale grey with age, and up to 1.5 cm high. Sporangiophores are hyaline to faintly pigmented, simple or sometimes branched arising solitary from the stolons, in groups of three, or in whorls of up to seven. The genus Absidia is characterized by a differentiation of the hyphae into arched stolons bearing more or less verticillate sporangiophores at the internode, and rhizoids formed at the point of contact with the substrate (at the node). This feature separates species of Absidia from the genus Rhizopus, where the sporangia arise from the nodes and are therefore found opposite the rhizoids. The sporangia are relatively small, globose, pyriform- or pear-shaped and are supported by a characteristic funnel-shaped apophysis. This distinguishes Absidia from the genera Mucor and Rhizomucor, which have large, globose sporangia without an apophysis.

The most commonly isolated species is Absidia corymbifera. It is the only recognized pathogen among the other Absidia species. Some of the other Absidia species are Absidia coerulea, Absidia cylindrospora, Absidia glauca, and Absidia spinosa.Rhizoids are very sparingly produced and may be difficult to find without the aid of a dissecting microscope to examine the colony on the agar surface. Sporangia are small (10-40 um in diameter) and are typically pyriform in shape with a characteristic conical-shaped columella and pronounced apophysis, often with a short projection at the top.

Toxin Production

Absidia corymbifera is a common human pathogen, causing pulmonary,

rhinocerebral, disseminated, CNS or cutaneous types of infection. It is also

often associated with animal disease, especially mycotic abortion. A.

corymbifera has a world-wide distribution mostly in association with

soil and decaying plant debris. The most serious infection associated

mycoses involved with absidia is Zygomycosis (further

explanation below).

Absidia species are

filamentous fungi that are cosmopolitan and ubiquitous in nature as common

environmental contaminants. They are usually found in food, plant debris and

soil, as well as being isolated from foods and indoor air environment. They

often cause food spoilage like on decaying vegetables in the refrigerator

and on moldy bread.

Health Effects

According to the study of Microbiology and Immunology On-line, the Absidia

species is one of the three most common genera that can cause

Zygomycosis which also known as

mucormycosis and phycomycosis.

Zygomycosis is an acute inflammation of soft tissue, usually with fungal

invasion of the blood vessels. This rapidly fatal disease is caused by

several different species in this class. The zygomycetes, like the

Candida species, are ubiquitous and rarely cause

disease in an immunocompetent host. Some characteristic underlying

conditions which cause susceptibility are:

diabetes, severe

burns, immunosuppression or intravenous drug use. Another common health

effect of absidia species, is Rhinocerebral infections. This disease

is frequently seen in the uncontrolled diabetic.

These fungi have a tendency to

invade blood vessels (particularly arteries) and enter the brain via the

blood vessels and by direct extension through the cribiform plate.

Rhinocerebral infections are usually fulminant and frequently fatal.

This is why they cause death so quickly.

Absidia species may also cause mucorosis in immune compromised

individuals. Mucurosis is an

infection with tissue invasion by broad, nonseptate, irregularly shaped

hyphae of diverse fungal species such as Absedia species. The

sites of infection are the lung, nasal sinus, brain, skin and eye (Mycotic

Keratitis-infection of cornea which can lead to blindness). Infection may

have multiple sites. One species of Absidia which is the Absidia

cormbifera has been an invasive infection agent in AIDS and neutropenic

patients, as well as, agents of bovine mycotic abortions, and feline

subcutaneous abscesses.

Macroscopic Features

Absidia corymbifera grows rapidly. The rapid growing, flat, woolly to cottony, and olive gray colonies mature within 4 days. The diameter of the colony is 3-9 cm following incubation at 25°C for 7 days on potato glucose agar. The texture of the colony is typically woolly to cottony. From the surface, the colony is grey in color. The reverse side is uncolored and there is no pigment production. Absidia corymbifera is a psychrotolerant-thermophilic fungus. It grows more rapidly at 37°C than at 25°C. Its maximum growth temperature is as high as 48 to 52°C. The growth of Absidia corymbifera is optimum at 35-37°C and at a pH value of 3.0 to 8.0.

Further reading

- Abdel-Gawad, K.M., & Zohri, A.A., Fungal flora and mycotoxins of six kinds of nut seeds for human consumption in Saudi Arabia, Mycopathologia 124 (1993) 55-64.

- Aisner, J., Schimpff, S.C., Bennett, J.E., Young, V.M., Wiernik, P.H., Aspergillus infections in cancer patiens. Association with fireproofing materials in a new hospital. J.Am. Med. Assoc. 235 (1976) 411-412.

- Ajello, L., Hyalohyphomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis: two global disease entities of public health importance. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1(1986) 243-251.

- Al-Suwaine, A.S., Bahkali, A.H., Hasnain, S.M., Seasonal incidence of airborne fungal allergens in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Mycopathologia 145(1999)15-22.

- Alberts, B., Bray, D., Lewis, J., Raff, M., Roberts, K.,Watson, J.D., in "Molecular Biology of the Cell", published by Garland Publishing, Inc, 1983.

- Ali, M.I., Salama, A.M., Ali, M.T., Possible role of solar radiation on viability of some air fungi in Egypt. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Parasitendkd. Infektionskr. Hyg. 131 (1976) 757-759.

- Alexopoulos, C.J., Mims, C.W., Blackwell, M., Introductory mycology 4th ed. John Wiley, New York, 1996, 868.

- American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygtienists, (ACGIH) Cincinattati, Ohio 1989, Guidelines for the assessment of bioaerosols in the indoor environment.

- Anaissie, E., Kantarjian, H., Jones, P., Barlogie, B., Luna, M., Lopez-Berestein, G., Bodey, G., Fusarium. A newly recognized fungal pathogen in inmunosuppresed patiens. Cancer 57 (1986) 2141-2145.

- Andersen, A.A., 1958. New sampler for the collection, sozing, and enumeration of viable airborne particles. J. Bacteriol. 76 (1958) 471-484.

- Arnow, P.M., Andersen, R.L., Mainous, P.D., Smith, E.J., Pulmonary aspergillosisi during hospital renovation. Am Rev. Resp. Dis. 118 (1978) 49-53.

- Arnow P.M,, Sadigh, M., Costas, C., Weil, D., Chudy, R., Endemic and epidemic aspergillosis associated with in-hospital replication of Aspergillus organisms. J Infect Dis 164 (1991) 998-1002.

- Arx, J.A., Guarro, J., and Figueras, M.J., The ascomycete genus Chaetomium. Nova Hedwigia Beiheft 14 (1986) 1-162.

- Arx, J.A.von, Rodriguez de Miranda, L., Smith, M.T., and Yarrow, D., The genera of Yeasts and Yeast like fungui. C.B.S., Stud. Mycol. 14 (1977).

- Bandoni, R.J., Aquatic hyphomycetes from terrestrial litter. In: Wicklow, D.T., Carrol, G.C., eds. The fungal comunity. Its organization and role in the ecosystem. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc., 1981. 693 - 708.

- Bissett, J., 1984, 1991, A revision of the genus Trichoderma I,II,III Can. J. Bot. 62 (1991) 924-931; Can.J.Bot. 69 (1991) 2357-2372; Can. J. Bot. 69 (1991) 2373-2417.

- Bocquet, P., Brucker, G., Integrated struggle against aspergillosis at the level of a single hospital or a hospital cluster. Pathol Biol (Paris) 42(1994)730-736.

- Burnett, H.L., and Hunter, B.B., Illustrated Genera of imperfect Fungi. MacMillan Publ. Co., Amsterdam. 1987.

- Bodey, G.P., Vartivarian, S., Aspergillosis, Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., 8 (1989) 413-437.

- Burge, H.A., Boise, R.J., Rutherfor, J.A., and W.R. Solomon. Comparative recoveries of airborne fungus spores by viable and non viable modes of vollumetric collection. Mycopathologia 61(1977)27-33.

- Burge, H.A., and W.R. Solomon. Sampling and analysis of biological aerosols. Atmos. Environm. 21(1987)451-456.

- Burgess, L.W., Liddell, C.M., Summerell, B.A., Laboratory manual for Fusarium research, 2nd ed. University of Sydney, Sydney. 1988.

- Burton, J.R., Zachery, J.B., Bessin, R., et al Aspergillosis in four renal transplant recipients. Ann. Intern. Med. 77 (1972) 383-388.

- Buttner, M.P., Stetzenbach, L.D., Monitoring airborne fungal spores in an experimental indoor environment to evaluate sampling methods and the effects of human activity on air sampling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59 (1993) 219-226.

- Calvo, M.A., Guarro, J., Suarez, G., Ramirez, C. Airborne fungi in Barcelona city (Spain). Mycopathology 71 (1980) 41-43.

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L., Delgado, R., Calderón-Gardueñas, A., Meneses, A., Ruiz, L.M., De La Garza, J., Acuna, H., Villareal-Calderón A., Raab-Traub, N., Devlin, R., Malignan neoplasms of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses: a series of 256 patients in Mexico City and Monterrey. Is air pollution the missing link? Otrolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 122 (2000) 499-508.

- Carmichael, J.W., Chrysosporium and some other aleuriosporic hyphomycetes. Can. J. Bot. 40 (1962) 1137-1173.

- Carmichael, J.W., Kendrick, W.B., Connors, I.L., and Sigler, L., Genera of Hyphomycetes. University Alberta Press, Edmonton, 1980, 386 pp.

- Cifuentes Blanco, J., M. Villegas Ríos, J.L. Villareal-Ordáz and S. Sierra Galván. Diversity of macromycetes in pine-evergreen oak forest in Neovolcanic Axis, Mexico. En Mycology in Sustainable Development: Expanding Concepts, Vanishing Borders, eds. M.E.Palm and I.H. Chapela, Parkway Publ., Boone, N.C.

- Cole, G.T., and Kendrick, B., Taxonomic studies of Phialophora. Mycologia 65(1973)661-688.

- Cooley, J.D., Wong, W.C., Jumper, C.A., Straus, D.C., Correlation between the prevalence of certain fungi and sick building sindrom. Occup. Environ. Med. 55 (1998) 579-584.

- Cornet, M., Levy, V., Fleury, L., Lortholary, J., Barquins, S., Coureul, M.H., Deliere, E., Zittoun, R., Brucker, G., Bouvet, A., Efficacy of prevention by high-efficiency particulate air filtration or laminar airflow against Aspergillus airborne contamination during hospital renovation. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 20 (1999) 508-513.

- Cox & Wathes, Bioaerosols handbook, 1994.

- Dharmage, S., Bailey, M., Raven, J., Mitakakis, T., Thien, F., Forbes, A.,Guest, D., Abramson, M., Walters, E.H., Prevalence and residential determinants of fungi within homes in Melbourne, Australia, Clin Exp Allergy 29(1999)1481-1489.

- Davis, R., Summerbell, R., Haldane, D., Dufur, A., Yu, K., Broder, I., Dales, R., Kirkbride, J., Kauri, T., Robertson, W., Damant, L.; Federal - Provincial Working group on mycological Air quality in public buildings; Fungal contamination in public buildings: A guide to recognition and Management. Health Canada, 1995.

- De Hoog G.S., Hermanides-Nijhof, E.J., The black yeast and aallied hyphomycetes. Stud. Mycol. 15 (1977) 1-222. Citado por clasificación de levaduras.

- Domsch K.H., Gams, W., Anderson, T.H. Compendium of soil fungi. New York: Academic Press, 1980. Citado por screening de especies

- Domsch, K.H., W. Gams, and T.H. Anderson. 1980. Compendium of soil fungi. Volume 1. Academic Press, London, UK.

- Emmanuel, S.C.,Impact to lung health of haze from forest fires: the Singapore experience. Respirology 5 (2000) 175-182.

- Ezeonu, I.M., Price, D.L., Simmons, R.B., Crow, S.A., Ahearn, D.G., Fungal production of volatiles during growth on fiberglass. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60 (1994) 4172-4173.

- Fiorina, A., Legnani, D., Fasano, V., Cogo, A., Basnyat, B., Passalacqua, G., Scordamaglia, A., Pollen mite and mould samplings by a personal collector at high altitude in Nepal. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 8 (1998) 85-88.

- Flynn PM, Williams BG, Hetherington SV, Williams BF, Giannini MA, Pearson TA, Aspergillus terreus during hospital renovation. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1993 Jul;14(7):363-5.

- Freire, F.C., Kozakiewicz, Z., Paterson, R.R., Mycoflora and mycotoxins of Brazilian cashew kernels. Mycopathologia 145 (1999) 95-103.

- Fresenius, G., 1850-1863 Beiträge zur Mykologie 111pp, 13 plates. H.L., Brönner, Frankfurt.

- Furuhashi M, Efficiency of bacterial filtration in various commercial air filters for hospital air conditioning. Bull Tokyo Med Dent Univ. 25 (1978) 147-155.

- Gage, A.A., Dean, D.C., Schimert, G., Minsley, N., Aspergillus infection after cardiac surgery. Arch. Surg. 101 (1970) 384-387.

- Garrett, M.H., Rayment, P.R., Hooper, M.A., Abramson, M.J., Hooper, B.M., Indoor borne fungal spores, house dampness and associations with environmental factors and respiratory health in children. Clin. Exp. Allergy 28 (1998) 459-467.

- Gonzalez Glez. Minero, F.J., Candau, P., Gonzalez Glez Romano, M.L., Romero, F., A study of the aeromycoflora of Cadiz: relationship to anthropogenic activity. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2 (1992) 211-215.

- Gordon, G., Axelrod, J.L., Case report: prosthetic valve endocarditis caused by Pseudallescheria boydii and Clostridium limosum. Mycopathologia 89 (1985) 12-134.

- Gravesen S., Nielsen, P.A., Iversen, R., Nielsen, K.F., Microfungal contamination of Dump Buildings. Examples of risk constructions and risk materials. Environ. Health Perspect 107 (1999) 505-508.

- Green, V.W., D.Vesley, R.G., Bond, R.G., and Michaelsen. Microbiological contamination of hospital air. Appl. Microbiol. 10 (1962) 561-566.

- Grosse G, L'Age M, Staib F., Peracute disseminated course of fatal Aspergillus fumigatus infection in liver failure and corticoid therapy. A case report on the epidemiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis of the systemic course of Aspergillus infections. Klin Wochenschr 63 (1985) 523-528.

- Guyton, A.C. and Hall, J.E., in pp 481, 531, 532 of "Textbook of Medical Physiology" ed McGraw-Hill-Interamericana de España, 1996.

- Hancock, T.,Creating health and health promoting hospitals: a worthy challenge for the twenty-first century. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv. 12 (1999) VIII-XIX.

- Hawksworth, D.L. and Kirsop, B.E., Ed. Living resources for biotechnology, Filamentous fungi, Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Hawksworth, D.L., The fungal dimension of biodiversity: magnitude, significance, and conservation. Mycol. Res. 95(1991) 641-655.

- Hesler, L.R., and A.H. Smith, North American species of Lactarius. Univ. Michigan Press, Ann Arbor. xii+841pp.

- Hoog, G.S. de, and Guarro, J., Atlas of Clinical fungi, C.B.S., Baarn, The Netherlands. 1995.

- Hiipakka DW, Buffington JR1. Resolution of sick building syndrome in a high-security facility. Appl Occup Environ Hyg 2000 Aug;15(8):635-43.

- Hirst, Ann. appl. Biol. 39(1952)257.

- Hudson, H.J., Aspergilli in the air spore at Cambridge, Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 52 (1969)153-159.

- Isselbacher, K.J., Braunwald, E., Wilson, J.D., Martin, J.B., Fauci, A.S., Kasper, D.L., en Harrison, Principios de Medicina Interna, 13ª Ed. Interamericana Mc Graw-Hill, 1994. pp. 1318... Octava parte

- Jager E, Ruden H, Zeschmar-Lahl, B., Composting facilities. 2. Aerogenic microorganism content at different working areas of composting facilities. Zentralbl. Hyg. Umweltmed. 196 (1994) 367-379.

- Jimenez, M., Mateo, R., Querol, A., Huerta, T., Hernandez, E., Mycotoxins and mycotoxigenic moulds in nuts and sunflower seeds for human consumption. Mycopathologia 115 (1991) 122-128.

- Jones, W., Morring, K., Morey, P., Sorensen, W., Evaluation of the Andersen viable impactor for single stage sampling. Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. J., 46 (1985) 294-298.

- Kendrick, B., Key to the genera of the hyphomycetes. Mycologue, Waterloo. 1994, 107 pp.

- Krasinski, K., Holzman, R.S., Hanna, B., Greco, M.A., Graff, M., Bhohal, M., Nososcomial fungal pulmonary infections (Zygomycetes, Aspergillus sp.) developed in two premature infants in a special care unit (SCU) adjacent to an area of renovation. Infect. Control, 6 (1985) 278-282.

- Kreger-van Rij, N.J.W., The yeast, a taxonomic study, Elsevier Sci. Public, Amsterdam 1984. Citado por clasificación de levaduras.

- Kwon-Chung, K.J. and J.E. Bennett. 1992. Medical Mycology. Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia and London.

- Kyriakides, G.K., Zinnman, H.H., Hall, W.H., Arora, V.K., Lifton, J., DeWolf, W.C., Miller, J., Immunologic monitoring and aspergillosis in renal transplant patients., Amer J Surg 131 (1976) 246-252.

- Largent, D.L., How to identify Mushrooms to genus 1._ Macroscopic Features.Mad River Press, Eureka, Calif., 86 pp.

- Largent, D.L., and Baroni, T.J., How to identify Mushrooms to genus 6._ Modern genera. Mad River Press, Eureka, Calif.1986, vi+277 pp.

- Largent, D.L., and Thiers, H.D., How to identify Mushrooms to genus 2._ Field identification of genera. Mad River Press, Eureka, Calif. 1977, vi+32 pp.

- Largent, D.L., Johnson, D., and Watling. 1977 , How to identify Mushrooms to genus 3._ Microscopic features. Mad River Press, Eureka, Calif. 1988, viii+148 pp.

- Lentino, J.R., Rosenkranz, M.A., Michaels, J.A:, Kurup, V.P., Rose, H.D., Rytel, M., Nosocomial Aspergillosis. A retrospective review of airborne disease secondary to road construction and contaminated air conditioners. Amer. J. Epidemiol. 116 (1982) 430-437.

- Lie, T.S., Hofer, M.,Hohnke, C., Krizek, L., Kuhnen, E., Iwantscheff, A., Koster, O., Overlack, A.,Vogel, J., Rommelsheim, K., Aspergillosis following liver transplantation as a hospital infection. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 112 (1987) 297-301.

- Loo, V.G., Bertrand, C., Dixon, C., Vitye, D., DeSalis, B., McLean, A.P., Brox, A., Robson, H.G., Control of construction-associated nosocomial aspergillosis in an antiquated hematology unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 17 (1996) 360-364.

- López-Martinez, R., Ruiz Sanchez, D., Guadalupe Huerta, José, Esquenaze, A., Alvarez, Mª.T. Variación estacional de hongos productores de alergía en el sur de la ciudad de México. Allergol. et Immunopathol. 14 (1986) 43-48.

- Loudon KW, Coke AP, Burnie JP, Shaw AJ, Oppenheim BA, Morris CQ. Kitchens as a source of Aspergillus niger infection. J. Hosp. Infect. 32 (1996) 191-198.

- Mahgoub H. A., Prevalence of airborne Aspergillus flavus in Khartoum (Sudan) Aispora with reference to dusty weather and inoculum survival in simulated summer conditions. Mycopathologia 104 (1988) 137-141.

- Mahieu LM, De Dooy JJ, Van Laer FA, Jansens H, Ieven MM, A prospective study on factors influencing aspergillus spore load in the air during renovation works in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Hosp Infect 2000 Jul;45(3):191-7.

- McGrath, J.J., Wong, W.C., Cooley, J.D., Straus, D.C., Continually measured fungal profiles in sick building syndrome. Curr. Microbiol. 38(1999)33-36.

- Miller, O.K., Jr. And Miller, H.H., Gasteromycetes. Morphological and development features with keys to the Orders, Families, and Genera. Mad River Press, Eureka, Calif. X+157 pp.

- Nakajima T, Azuma E, Hashimoto M, Toyoshima K, Hayashida M, Komachi Y., Factors aggravating bronchial asthma in urban children (I)--The involvement of indoor air pollution. Nippon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 45 (1998) 407-422.

- Nielsen, K.F., Gravesen, S., Nielsen, P.A., Andersen, B., Thrane, U., Frisvad, J.C., Production of mycotoxins on artificially and naturally infested building materials. Mycopathologgia 145 (1999) 43-56.

- Nolard, N., Links between risks of aspergillosis and environmental contamination. Review of the literature. Pathol Biol (Paris) 42 (1994) 706-710.

- Nolard, N., Invasive aspergillosis: nosocomial origin of epidemics. Review of the literature. Bull Acad Natl Med 180 (1996) 849-856.

- Paden, J. W., A centrifugation technique for separating ascospores from soil. Mycopathol. Mycol. Appl. 33 (1967) 382-384.

- Petersen, R.H., Checklist of fungi of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. National Park Service Management Report 29.

- Pieckkova, E., Jesenska, Z., Molds on house walls and the effect of their chloroform-extractable metaboliteson the respiratory cilia movement of one-day-old chicks in vitro. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 43 (1998) 672-678.

- Pitt, J., The genus Penicillium and its teleomorphic states Eupenicillium and Talaromyces, New York Academic Press, 1979.

- Prahl, P., Reduction of indoor airborn mould spores. Allergy 47 (1992) 362-365

- Raper, K.B., and Fennell, D.I., The genus Aspergillus, Ed. Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, Florida, 1965, pp. 239.

- Rhame, F.S., Prevention of nosocomial aspergillosis, J. Hosp. Infec. 18 (1991) 466-472. Aspergillus fumigatus, flavus, terreus.

- Rhame, F.S., Streifel, A.J., Kersey, J.H. Jr., McGlave, P.B., Extrinsic risk factors for pneumonia in the patient at high risk of infection. Am J Med 76 (1984) 42-52.

- Richardson MD, Rennie S, Marshall I, Morgan MG, Murphy JA, Shankland GS, Watson WH, Soutar RL. Fungal survelliance of an open haematology ward. J Hosp Infect 45 (2000) 288-292.

- Rose, H.D., Varkey, B., Deep mycotic infection in the hospitalized adult: a study of 123 patiens. Medicine 54 (1975) 499-507.

- Rose, H.D., Hirsch S.R., Filtering hospital air decreases Aspergillus spore counts. Am. Rev. Resp. Dis. 119 (1979) 511-513.

- Rotstein C, Cummings KM, Tidings J, Killion K, Powell E, Gustafson TL, Higby D., An outbreak of invasive aspergillosis among allogeneic bone marrow transplants: a case-control study. Infect Control 6 (1985) 347-355.

- Rossman A.Y., Tulloss, R.E., O'Dell, T.E., Greg Thorn, R., in "Protocols for an all taxa biodiversity inventory of fungi in a Costa Rican conservation area", ed. Parkway Publishers, Inc. Boone, N.C., USA, 1998, 195 pp.

- Ruutu P, Valtonen V, Tiitanen L, Elonen E, Volin L, Veijalainen P, Ruutu T., An outbreak of invasive aspergillosis in a haematologic unit. Scand J Infect Dis 19 (1987) 347-351.

- Salkin, I.F., McGinnis, M.R., Dykstra, M.J., Rinaldi, M.G., Scedosporium inflatum, an emerging pathogen J. Clin. Microbiol. 26 (1988) 498-503. Lo aislan de una biopsia ósea de una lesión osteomielítica de un niño de 6 años.

- Salama, A.M., Ali, M.I., El-Kirdassay, Z.H., Ali, T.M., A study of fungal radioresistance and sensitivity. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Parasitendkd. Infektionskr. Hyg. 132 (1977) 1-13.

- Samson, A., Occurrence of moulds in modern living and working environments, Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1 (1985) 54-61.

- Sayer, W.J., Shean, D.B., and Ghosseiri, J., Estimation of airborne fungal flora by the Andersen sampler versus the gravity settling plate.J. Allergy 44 (1969) 214-227.

- Seltzer, J.M., Biological contaminants. J Allergy Clin Immunol 94 (1994) 318-326.

- Sessa A, Meroni M, Battini G, Pitingolo F, Giordano F, Marks M, Casella P., Nosocomial outbreak of Aspergillus fumigatus infection among patients in a renal unit? Nephrol Dial Transplant 1996 Jul;11(7):1322-4.

- Shearer, C.A., The freshwater ascomycetes. Nova Hedwigia 56 (1993) 1-33.

- Sherertz, R.J., Belani, A., Kramer, B.S., Elfenbein, G.J., Weiner R.S., Sullivan, M.L., Thomas, R.G., Samsa, G.P., Impact of air filtration on nosocomial Aspergillus infections. Unique risk of bone marrow transplant recipients. Am. J. Med. 83 (1987) 709-718.

- Simmons, E.G., Typification of Alternaria Stemphylium, and Ulocladium, Mycologia, 59 (1967) 67-92.

- Simmons, R.B., Price, D.L., Noble, J.A., Crow, S.A., Ahearn, D.G., Fungal colonization of air filters from hospitals. Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. J. 58 (1997) 900-904.

- Sivanesan, A., The bitunicate Ascomycetes and their anamorphs. J.Cramer, Vaduz, Germany. 1984, 701 pp.

- Sorenson, W.G., Fracer, D.G., Jarvis, B.B., Simpson, J., and Robinson, V.A., Trichothecene mycotoxinsin aerosolized conidia of Stachybotrys atra. Appl. Environm. Microbiol. 53(1987)1370-1375.

- Streifel, A.J., Stevens, P.P., Rhame, F.S., In-hospital source of airborne Penicillium species spores. J Clin Microbiol 25 (1987) 1-4.

- Summerbell, R.C., Krajden, S., and Kane, J., Potted plants in hospitals as reservoirs of pathogenic fungi. Mycopathology 106 (1989) 13-22.

- Summerbell, R.C., The heterobasidiomycetous yeast genus Leucosporidium in an area of temperate climate. Can.J.Bot 61 (1983) 1402-1410.

- Summerbell, R.C., Protocols for Investigation of Indoor Fungal Amplifiers, www.summerbell, 1999.

- Taplin, D., Mertz, P.M., Flower vases in hospitals as reservoirs of pathogens. The lancet II(1973)1279-1281.

- Thrower, S.L., Hong Kong Lichens, Urban council, Hong Kong, 1988., incluye fotos en color de 140 especies.

- Trujillo-Jurado, D., Infante García-Pantaleón, F., Galán Soldevilla, C., Domínguez Vilches, E., Seasonal and daily variation of Aspergillus Mich. Ex Fr. spores in the atmosphere of Códoba (Spain). Allergol. et Immunopathol., 18(1990) 167-173.

- Verhoeff A.P., van Wijnen, J.H., Boleij J.S., Brunekreef B.,van Reenen-Hoekstra E.S., Samsom, R.A; Allergy 45 (1990) 275-284.

- Verhoeff A.P., van Wijnen, J.H., Brunekreef B., Fischer, P., van Reenen-Hoekstra E.S., & Samsom, R.A., Allergy 47 (1992) 83-91.

- Verhoeff A.P., van Wijnen, J.H., Fischer, P., Brunekreef B., Boleij J.S., van Reenen-Hoekstra E.S., Samsom, R.A., Presence of viable mould propagupes in the indoor air of houses. Toxicol. Ind. Health 6 (1990) 133-145.

- Vermorel-Faure, O., Lebeau, B.,Malleret, M.R., Michallet, M., Brut, A., Ambroise-Thomas, P., Grillot, R., Risque fongique alimentaire au cours de l'agranulocytose. Controle mycologique de 273 aliments proposés à des malades hospitalisés en secteur stérile, La Presse Médicale 22 (1993) 157-160.

- Vleggaar, R., Steyn, P.S., Nagel, D.W., Constitution and absolute configuration of austdiol, the main toxic metabilite from Aspergillus ustus. J. Chem. Soc. [Perkin 1] 1(1974) 45-49.

- Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B., and Kohlmeyer, J., How to prepare truly permanent microscopic slides. The Mycologist 10 (1996)107-108.

- Walsh, T.J. and Dixon, D.M. Nosocomial aspergillosis: environmental microbiology, hospital epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 5 (1989) 131-142.

- Woods GL, Davis JC, Vaughan WP., Failure of the sterile air-flow component of a protected environment detected by demonstration of Chaetomium species colonization of four consecutive immunosuppressed occupants. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 10(1988)451-456.

- Yoshimura, I., Lichen Flora of Japan in Colour, Hoikusha Publ. Co., Osaka. 349 pp. Está en Japonés pero incluye muchas ilustraciones.

- Zak, J.C., and Wicklow, D.T., Response of carbonicolous Ascomycetes to aerated steam temperatures and treatment intervals. Canad. J. Bot 56 (1978) 2313-2318.

©2001-2003 Mold-Help

All rights reserved.