The Insurance Game

San Diego, CA – Property insurers use secret tactics to cheat customers out of payments–as profits break records.

Julie Tunnell remembers standing in her debris-strewn driveway when the tall man in blue jeans approached. Her northern San Diego tudor-style home had been incinerated a week earlier in the largest wildfire in California history. The blaze in October and November 2003 swept across an area 19 times the size of Manhattan, destroying 2,232 homes and killing 15 people. Now came another blow.

A representative of State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co., the largest home insurer in the U.S., came to the charred remnants of Tunnell’s home to tell her the company would pay just $220,000 of the estimated $306,000 cost of rebuilding the house.

“It was devastating. I stood there and cried,” said Tunnell, 42, who teaches accounting at San Diego City College. “I felt absolutely abandoned.”

Tunnell joined thousands of people in the U.S. who already knew a secret about the insurance industry: When there’s a disaster, the companies homeowners count on to protect them from financial ruin routinely pay less than what policies promise. Insurers often pay 30-60 percent of the cost of rebuilding a damaged home–even when carriers assure homeowners they’re fully covered, thousands of complaints with state insurance departments and civil court cases show.

Paying out less to victims of catastrophes has helped produce record profits. In the past 12 years, insurance company net income has soared–even in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, the worst natural disaster in U.S. history. Property- casualty insurers, which cover damage to homes and cars, reported their highest- ever profit of $73 billion last year, up 49 percent from $49 billion in 2005, according to Highline Data LLC, a Cambridge, Massachusetts-based firm that compiles insurance industry data.

The 60 million U.S. homeowners who pay more than $50 billion a year in insurance premiums are often disappointed when they discover insurers won’t pay the full cost of rebuilding their damaged or destroyed homes. Property insurers systematically deny and reduce their policyholders’ claims, according to court records in California, Florida, Illinois, Mississippi, New Hampshire and Tennessee. The insurance companies routinely refuse to pay market prices for homes and replacement contents, they use computer programs to cut payouts, they change policy coverage with no clear explanation, they ignore or alter engineering reports, and they sometimes ask their adjusters to lie to customers, court records and interviews with former employees and state regulators show. As Mississippi Republican U.S. Senator Trent Lott and thousands of other homeowners have found, insurers make low offers–or refuse to pay at all–and then dare people to fight back.

“It’s despicable not to make good-faith offers to everybody,” says Robert Hunter, who was Texas insurance commissioner from 1993 to ’95 and is now insurance director at the Washington-based Consumer Federation of America. “Money managers have taken over this whole industry. Their eyes are not on people who are hurt but on the bottom line for the next quarter.”

The industry’s drive for profit has overwhelmed its obligation to policyholders, says California Lieutenant Governor John Garamendi, a Democrat. As California’s insurance commissioner from 2002 to ’06, Garamendi imposed $18.4 million in fines against carriers for mistreating customers. “There’s a fundamental economic conflict between the customer and the company,” he says. “That is, the company doesn’t want to pay. The first commandment of insurance is, ‘Thou shalt pay as little and as late as possible.'”

Although the tension between insurers and their customers has long existed, it was in the 1990’s that the industry began systematically looking for ways to increase profits by streamlining claims handling. Hurricane Hugo was a major catalyst. The 1989 storm, which battered North and South Carolina, left the industry reeling from $4.2 billion in claims. In September 1992, Allstate Corp., the second-largest U.S. home insurer, sought advice on improved efficiency from McKinsey & Co., a New York-based consulting firm that has advised many of the world’s biggest corporations, according to records in at least six civil court cases.

State Farm, based in Bloomington, Illinois, and Los Angeles-based Farmers Group Inc., the third-largest home insurer in the U.S., also hired McKinsey as a consultant, court records show.

McKinsey produced about 13,000 pages of documents, including PowerPoint slides, in the 1990’s, for Northbrook, Illinois-based Allstate. The consulting firm developed methods for the company to become more profitable by paying out less in claims, according to videotaped evidence presented in Fayette Circuit Court in Lexington, Kentucky, in a civil case involving a 1997 car accident.

One slide McKinsey prepared for Allstate was entitled “Good Hands or Boxing Gloves,” the tape of the Kentucky court hearing shows. For 57 years, Allstate has advertised its employees as the “Good Hands People,” telling customers they will be well cared for in times of need. The McKinsey slides had a new twist on that slogan. When a policyholder files a claim, first make a low offer, McKinsey advised Allstate. If a client accepts the low amount, Allstate should treat the person with good hands, McKinsey said. If the customer protests or hires a lawyer, Allstate should fight back.

“If you don’t take the pittance they offer, they’re going to put on the boxing gloves and they’re going to batter injured victims,” plaintiffs attorney J. Dale Golden told Judge Thomas Clark at the May 12, 2005, hearing in which the lawyer introduced the McKinsey slides.

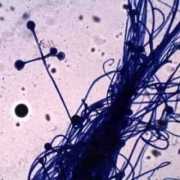

One McKinsey slide displayed at the Kentucky hearing featured an alligator with the caption “Sit and Wait.” The slide says Allstate can discourage claimants by delaying settlements and stalling court proceedings. By postponing payments, insurance companies can hold money longer and make more on their investments– and often wear down clients to the point of dropping a challenge. “An alligator sits and waits,” Golden told the judge, as they looked at the slide describing a reptile.

McKinsey’s advice helped spark a turnaround in Allstate’s finances. The company’s profit rose 140 percent to $4.99 billion in 2006, up from $2.08 billion in 1996. Allstate lifted its income partly by paying less to its policyholders. Allstate spent 58 percent of its premium income in 2006 for claim payouts and the costs of the process compared with 79 percent in 1996, according to filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. The payout expense, called a loss ratio, changes each year based on events such as natural disasters; overall, it’s been decreasing since Allstate hired McKinsey.

Investors have noticed. Allstate’s stock price jumped fourfold to $60.95 on July 11 from its closing price on June 3, 1993, the day of its initial public offering. During the same period, the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index rose threefold. State Farm’s profits have doubled since 1996 to $4.8 billion in 2006. Because State Farm is a mutual company, meaning it’s owned by its policyholders, it doesn’t have shares that trade publicly.

“This is about as good a stretch as I’ve seen,” says Michael Chren, who manages $1.5 billion at Allegiant Asset Management Co. in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, and has followed the property-casualty industry for 20 years. The industry’s performance during the past five years has been superb, even with payouts for Katrina, he says. “All the stars have been in alignment. There has been decent pricing of products and an extremely attractive and very low loss ratio.”

Reducing payouts is just one way the industry has improved profits. Carriers have also raised premiums and withdrawn from storm-plagued areas such as the Gulf Coast of the U.S. and parts of Long Island, New York–to lower costs and increase income, says Amy Bach, executive director of United Policyholders, a San Francisco-based group that advises consumers on insurance claims. “What this says is that the industry has been raking in spectacular profits while they’re getting more and more audacious in their tactics,” she says.

Allstate spokesman Michael Siemienas says the company won’t comment on what role McKinsey played in lowering the insurer’s loss ratio and boosting its profits. Allstate did change the way it handles homeowners’ insurance claims, he says. “In the early 1990s, Allstate redesigned its claims practices to more efficiently and effectively handle claims and better serve our customers,” he says.

“Allstate’s goal remains the same: to investigate, evaluate and promptly resolve each claim based on its merits,” Siemienas says. “Allstate believes its claim processes support this goal and are absolutely sound.”

McKinsey doesn’t discuss any of its work for clients, spokesman Mark Garrett says.

Jerry Choate, Allstate’s chief executive officer from 1995 to ’98, said at a news conference in New York in 1997 that the company’s new claims-handling process had reduced payments and increased profit, according to a report in a March 1997 edition of National Underwriter magazine. Insurers can’t make significantly more money just from cutting sales costs, he told reporters. “The leverage is really on the claims side,” Choate said. “If you don’t win there, I don’t care what you do on the front end. You’re not going to win.”